Estudios en Seguridad y Defensa, 20 (39), 11-36

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25062/1900-8325.4967

Geopolitics of Rare Earth Elements: A Descriptive Analysis from the National Security and Defense Framework

Geopolítica de tierras raras: un análisis descriptivo desde el marco de seguridad y defensa nacionales

U.S. Naval War College, Newport (RI), United States of America

APA CITATION:

García Torres, J. A. (2025). Geopolitics of Rare Earth Elements: A descriptive analysis from the national security and defense framework. Estudios en Seguridad y Defensa, 20(39), 11-36. https://doi.org/10.25062/1900-8325.4967

Scientific Research Article

Received: March 13, 2025 • Accepted: April 8, 2025

Contact: Jorge Alfonso García Torres jorgartorr@gmail.com

Abstract

This article analyzes the media coverage (radio, press, television and social networks) of public opinion in the context of the Colombian internal armed conflict. It presents the main characteristics of the conflict reflected by these media and their influence on the image of the actors of the conflict in the public opinion, particularly on the effectiveness and legitimacy of the Armed Forces. With a mixed, non-exhaustive descriptive methodology, based on a survey of experts, this analysis combines objective and subjective visions with macro and micro approaches to the issue. It shows how the attitude and position of the media in the conflict has varied in the face of the changes of the contending forces, following their own logics before the public opinion; sometimes obsequious to armed groups and other times indifferent to the efforts of the Armed Forces.

Key words: Colombia; geopolitics; national security; Rare Earth Elements; resource curse; strategic minerals

Resumen

La geopolítica de tierras raras (REE) ha surgido como un eje estratégico para la seguridad y defensa nacional. En Colombia, este tema es incipiente y cuenta con una limitada producción académica. Una revisión de bases de datos indexadas como Scopus, Web of Science y Science Direct reveló la falta de estudios científicos sobre seguridad y enfoques experimentales. Este estudio, de carácter exploratorio, se basa en tres pilares: (1) análisis de antecedentes nacionales e internacionales sobre la geopolítica de los REE, con énfasis en la dinámica China-Estados Unidos; (2) aplicación del enfoque neofuncionalista y la teoría de la maldición de los recursos naturales para interpretar el fenómeno; (3) correlación entre la presencia de estos minerales en Colombia y variables socioeconómicas críticas. Los hallazgos demuestran la necesidad de una estrategia nacional de manejo y protección de estos recursos estratégicos.

Palabras Clave: Colombia; geopolítica; maldición de los recursos naturales; minerales estratégicos; seguridad nacional; tierras raras

Introduction

Rare Earths Elements (REE) are a geopolitical component insufficiently studied in the Colombian case. Research studies such as those by Álvarez and Trujillo (2020) and Mantilla et al. (2006) offer an initial exploratory perspective, analyzing REE from two viewpoints: geological and socio-scientific (security and national defense). As this research will show, there is limited production of knowledge about REE in the Colombian context. An analysis of publications in Scopus and Science Direct reveals that Colombia has not significantly contributed to scientific research, with limited knowledge generation in quantitative and non-quantitative experimental studies. The lack of epistemological development in geological and security analyses led to the question: How can the current security and defense framework be analyzed concerning national interests centered on the ‘geopolitics of REE’?

Three specific objectives were set to respond. The first was to analyze background information, which constituted a state-of-the-art analysis of the fundamental aspects, both structural and functional, related to the concept of REE. This section analyzed the subject using the epistemological geopolitics of REE as a precedent. With the inputs collected, the second part was developed, and a theoretical approach to the REE was developed using two approaches and/or perspectives: interpretation of REE through the understanding of the curse of natural resources and conceptualization of the problem identified with the theory of the multidimensional security approach. After analyzing the background and framing the conceptual and theoretical components, we worked on the final part, which dealt with the conceptual debate in Colombia about REE or territories with lanthanide tenure.

Methodology

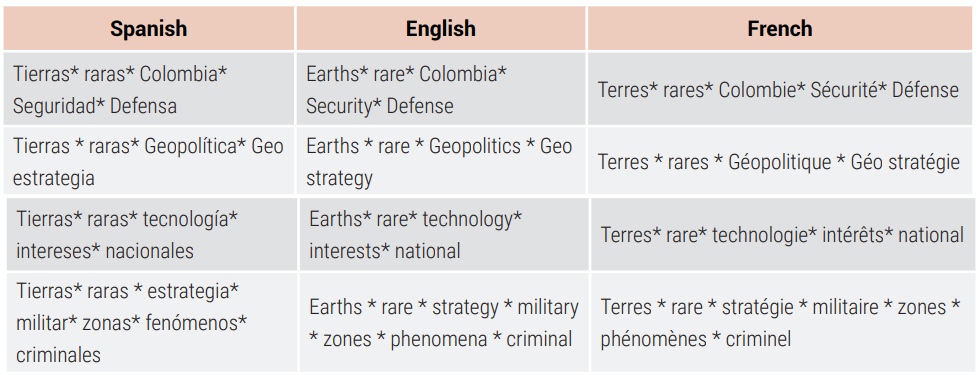

This research employed a qualitative, exploratory, and deterministic approach to analyze the issue of REE in Colombia. Despite lacking scientific and social research, this study utilized systematic literature review techniques to gather relevant data. To this end, the author proposed a first step: designing the search equation (Table 1).

Table 1. Search equations.

Source: Own elaboration

The equations included the Scopus, Web of Science, and Science Direct; obtaining 117 results, which were organized by author and database repetition using VOS viewer software. Figure 1 shows the results.

Figure 1. Connecting classified terms with VOSviewer.

Source: Own elaboration with VOSviewer.

The classification and connection of terms clarified the number of national and international sources of information related to the problem. The problem of REE is not only associated with the scientific field of experimental but also with the geopolitics of strategic natural resources, with theories such as the neo-realist curse of natural resources, and, of course, with the intersectoral fields of national security and defense. This section will examine the role of the current security and defense framework in relation to the concept of national interests focused on the “geopolitics of REE.”

REE, an Exogenous Analysis from Scientific Information Sources

REE are a topic of broad international discussion. Currently, the debate in this field is connected to scientific mining. Research on national security and defense is scarce. See Figure 2 to analyze the academic and scientific fields with the most significant involvement.

Figure 2. Research published by area.

Source: Information retrieved from SCOPUS (2022).

The segmentation of research shows that, first, the fields of materials science and planetary sciences have the highest number of publications. The defense sector or military sciences are not present as research categories. Four significant antecedents will emerge if the research approach encompasses an international scope. The first referenced publication is Geostrategic Consequences of China’s Hegemony in the REE Market, which Gabás (2020) authored. While the knowledge piece does not lean towards the experimental, it does address the topic from two points of view that are of interest to this exploratory cycle: the geopolitical and the geostrategic.

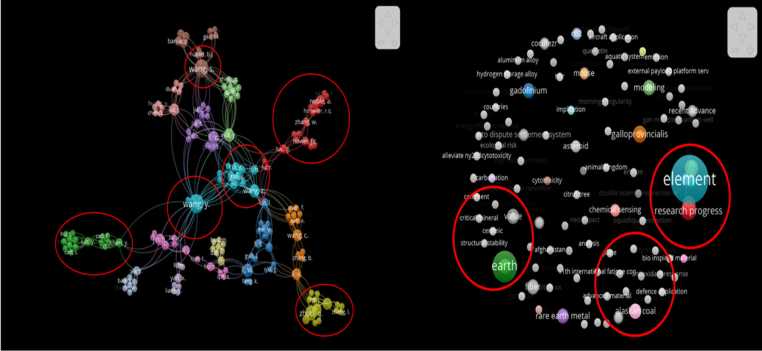

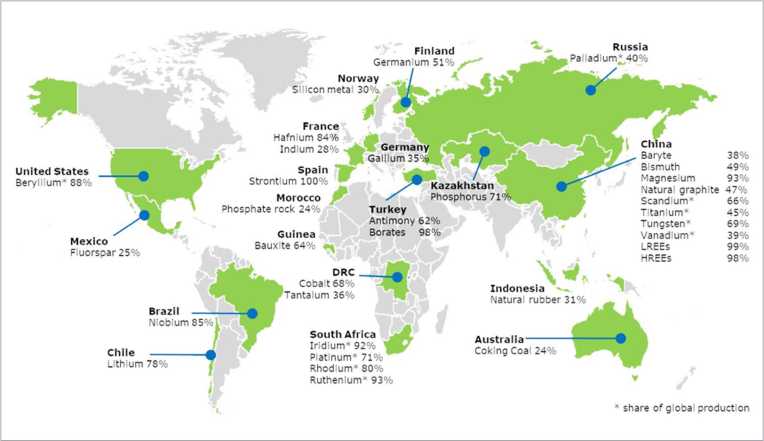

From a geo-strategic perspective, China’s strength is not only in its control over REE reserves but also in its dominance of processing and transformation, which are key to its hegemonic strategy. On a geopolitical scale, it has shown continued interest in acquiring this type of land (see Figure 3 to identify the extent of production globally) (Hyatt, 2024).

Figure 3. The wealthiest countries in REE reserves.

Source: The World Order (2021).

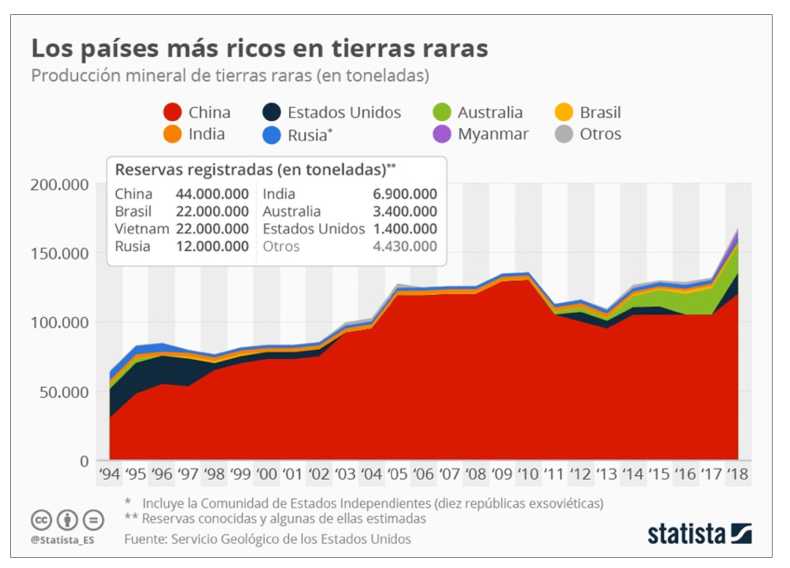

The importance of REE exploitation for China can be understood through two key factors. First, the demand for this type of lanthanide increased significantly, demarcating a core of high fluctuations between 1970 and 2020. In 2020, the demand for these minerals reached 140,000 tons, demonstrating a particular pattern with sales statistics (Hyatt, 2024). International growth related to the exploitation of rare minerals does not cease exponentially, as lanthanides are fundamental in developing consolidated technologies and others under experimentation (Haxel, 2002). In Figure 4, macroeconomic historical events that produced significant cessation of international commercial transactions but did not affect the extraction and sale of REE can be identified.

Figure 4. Market factors and marketing of REE.

Source: Information retrieved from Perez (2018).

Second, it is necessary to analyze technological factors. China’s proportional reach into territories that possess REE suggests that its interest is strategic, persuasive, and strategic-dominant (Humphries, 2010; Hyatt, 2024). This is because the minerals located in this type of land are fundamental for the processing, designing, and invention of traditional technologies and technologies in the projection process (Gao et al., 2024). Lanthanides are important for generating advantages in a new energy competition framework. This is clearly stated by Reboredo (2021) in Las tierras raras, una pieza clave en el puzle de la energía. According to the author:

Today’s high technology relies on the elements of the REE, we would go back to 1960 if they did not exist. They are strategic elements militarily, and critical industrially; basic to energy management, consumption (lighting, magnets, vehicles), storage (batteries, hydrogen storage) and production (wind turbines, photovoltaic panels, nuclear reactors) [...] Scientific publications and author affiliations concerning black earths are dominated by Chinese records [...] such is the dominance that China sank prices and achieved a monopoly position (97% of world production, 2010; Western mining culture languishes) by exploiting its mine Baiyunebo, the largest in production/reserves on the planet. (Reboredo, 2021, p. 4)

Reboredo’s (2021) position deals with commercial monopolies. This argument is the first relevant element to justify REE massive and dominant exploitation. The second research disrupts the defense sector and makes it clear that the REE are not alien to the set of strategic lines present in the national security and defense scheme. It is entitled Will there be a war over REEs? Strategic resources at the center of the Sino-US conflict published by Bortolini (2020). Bortolini (2020) discusses the relationship between China’s capabilities and the supply requirements of certain countries and technology companies.

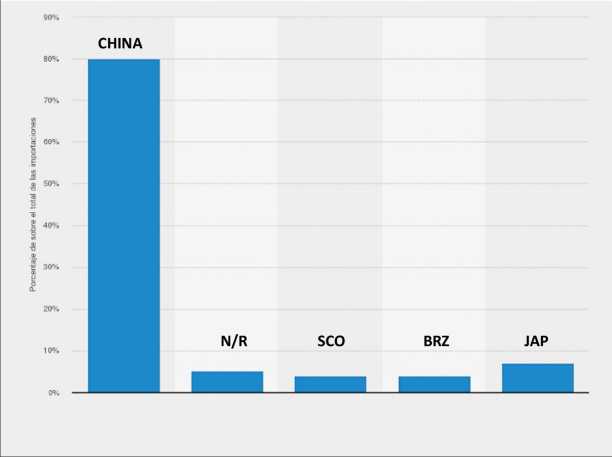

The United States is on that list, thus recalling that during 2019 it imported 90% of its lanthanides used in research and other developmental fields (Grasso, 2013; SWI, 2022). Such import came from China, and Figure 5 shows what Sanchez (2012) called mining-energy dependence.

Figure 5. Origin of U.S lanthanide imports.

Source: Information retrieved from Fernandez (2022).

The conflictual core analyzed by Bortolini (2020) does not conceptualize possible tensions of a hostile nature since this is not the focus that characterizes a competition for strategic natural resources; the author’s conception is closer to the development of new strategic lines, of geopolitical typology, with which to exercise international hegemony and control the macro commercial (Ghorbani et al., 2024).

Gadea-Ugarte (2020) explains that, like Bortolini (2020), the international dispute over REE is centered on market control rather than hostility, through the perspective of the Rare Metal War. The consequent implications, explaining Gadea-Ugarte (2020), range from affecting emerging markets subject to the creation of green tech to the disruption of “state-of-the-art military technologies” (Gadea-Ugarte, 2020, p. 39).

Gadea-Ugarte (2020) and Bortolini (2020) discuss the Market’s dominance. In this regard, and based on the assumption of pro-state macroeconomic control, the question arises: What is China’s dominance’s representative advantage regarding the REE? The answer has a neo-realist approach and is close to a construction that is not oligopolistic but monopolistic. Its purpose is to materialize state actions aimed at what Hirschman (1980) called economic interdependence. A sample hypothesis concerns determinations such as the reduction of sales and suspension of international transactions linked to the commercialization of REE between 2010 and 2011 (Martins, 2024).

In 2011, China provoked a series of macroeconomic controversies by reducing exports of REE; that reduction caused a circumstantial increase in prices on lanthanides, generating an increase in the cost/value of minerals such as oxide dysprosium, which went “from USD$102 to USD$2,150 in 2012” (Riesgo, 2020, p. 1). In the cited report, it is explained that China acknowledges apparent market manipulation. However, to discard the term apparent, this research turned to the analysis of the World Trade Organization, which defined the critical positions and macro-commercial complaints presented by the United States and Japan against China. This was due to the increase in costs and other tax variables on minerals belonging to the rare earth category (Martins, 2024) .

It is enough to look at the panel’s definition to understand commercial visions subject to the structure of a geoeconomic strategy oriented to the monopoly of minerals. According to the deliberative panel:

In light of the above, the Panel concludes that, in 2012, China imposed export duties ranging from 5% to 25% ad valorem on 58 REE, 15 tungsten products and nine molybdenum products.95 The Panel concludes that these products are not covered by Annex 6 of China’s Protocol of Accession. Accordingly, the Panel finds that China’s imposition of export duties on these products is inconsistent with Section 11, paragraph 3 of its Protocol of Accession. (World Trade Organization, 2014, p. 14)

It is necessary to agree that the variables involved in analyzing a possible monopoly are complex; however, it is sufficient to examine this background to establish two deductive points. First, that China has been developing new forms not of exploitation, but of appropriation, control and domination of REE, which are not related to territorial interventions or other forms of appropriation, but to the control of deposits, taking some advantage over technology-producing countries dependent on the importation of raw materials. Second, China assumes a posture technological-geopolitical based on the possession of commodities, their processing and subsequent market penetration (Martins, 2024). Both deductions lead to the third research, “The impact of REE on the international order”, published by Weber (2021).

Weber (2021)’s perspective focuses on two important aspects for the research. The first encompasses the international geopolitical factor contained in the REE, not because of their transformation, but because of the concentration of their deposits. China is not only dominant on an international scale but also hegemonic, and the stability of its foreign policy agenda depends on the material holdings of other states; this is the case of the European Union, the second explanatory aspect (Martins, 2024).

In its Foresight Plan for Critical Materials Resilience (2020), the European Commission (2020) states that the success factor for ensuring digital transformation processes by European states depends on the resilience and independence that the EU can form against international monopolies or oligopolies. China dominates these monopolies and oligopolies due to its extensive possession of this resource type, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Location of reserves REE.

Source: Information retrieved from the European Commission (2020)

It is noteworthy that one of the four strategic variables in the Foresight Plan is the search for REEs in third or attached States; in fact, committed action No. 9 states that the US should carry out strategic actions aimed at establishing international relations with States that have value chains related to the commercialization of REEs. It is worth noting that the focus is on African and Latin American countries (Dos Fuser, 2023).

The fourth research presents a state-of-the-art approach regarding the geoeconomics of rare critical minerals; Vekasi (2021) approaches REE and national security and defense to the international geoeconomic framework, but not from the relevance offered by the possession of this type of minerals exclusively but from the protection, safeguarding, and conservation of REE. The author explains how China extended its hegemonic will through the abundance of REE, facilitating macroeconomic control over international markets.

The conceptualization brings to this problem a security approach securitization, what to do or how to protect REE from international actors for dominant purposes (Wang, et.al., 2024). Well, this question remains unanswered; perhaps in research, Vekasi’s (2021) warnings exist, but there are mechanisms linked not only to protection but also to the factor. protectionism

Up to this point, the analysis of these four studies was adequate to understand the issue of REEs from two directions: the macroeconomic interest and the geopolitical interest in the dominance of territories with extensive deposits. Now, for the following part, the background search, once the problem of REE has been made explicit, is micro-focused on the management that Colombia has given to the issue from two points of view: security and defense in the sectors where there may be the existence of lanthanides and securitization limited to the safeguarding and protection of REE.

Lanthanides in the Colombian case do not have an extensive research nucleus, or at least not from the security and defense point of view. The research registered in databases and scientific indexes is focused on the initial and exploratory search of this type of minerals. A first precedent can be found in the research of Alvarez and Trujillo (2020). For both authors, land is a topic of interest in the framework of national security and defense for two reasons: On one hand, the countries that have REE do not have as many problems of public order or territorial insecurity as Colombia; hence, their research focuses on science, experimentation, or commercialization and not on security or armed protection.

On the other hand, the issue of REE in Colombia, from the point of view of the mining-energy industry, has not been rigorously investigated, which is why there is no relevant recognition compared to other types of minerals such as gold or coltan. Now, regarding the relationship between security and defense and REE, Alvarez and Trujillo (2020), explain the following:

Safeguarding immediate access to REE ensures that States can continue to reap the social, economic and political benefits of information, transportation, energy production and storage technologies. As such, REE are a strategic natural resource for which states are currently competing and will continue to compete for control in the years to come. A strategic natural resource is a commodity for which lack of access constitutes a security risk regarding economic prosperity and defense, as its lack can contribute to unfavorable economic and political outcomes for states. In this case, loss in REE would inhibit technological innovation, technological function, and technology productivity gains. (p. 14)

Although lanthanides in Colombia are not associated with a solid, explored, and/or determined market, they are subject to the national security and defense factor, especially because investigations already show the existence of REE in different state territories. One of these investigations is entitled “Identification of elements in REE in Colombian coals,” which was published by Henao (2019).

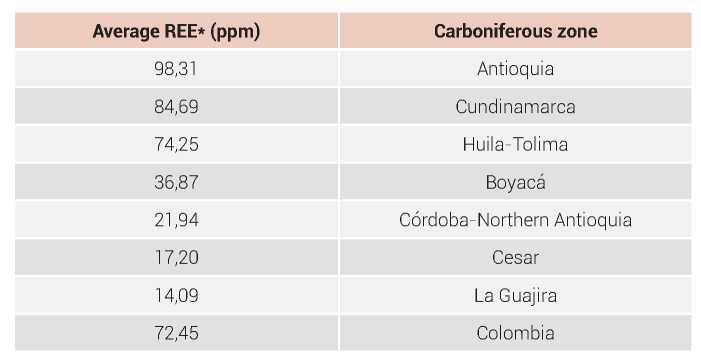

The sampling conducted by Henao (2019) was divided into four types: channel, borehole, production, and outcrop samples. The average search quantity, i.e., the standard of parts per million REE in coal, has a standard figure of 70.74 ppm (Henao, 2019, citing Ketris &Yudovich, 2009). This being the standard, the general findings of Henao (2019) are set out to understand which and how many REEs there might be in Colombia and over which areas they are located (Table 2).

Table 2. Standard found PPM.

Source: Information retrieved from Henao (2019). * Rare Earth Elements.

Table 2 shows that three regions have coal mining areas where the level of lanthanide exceeds the international standard of 70.74 ppm. These areas are Antioquia, Cundinamarca and Huila-Tolima. Relevant aspects, perhaps the most important, are that Henao’s (2019) is limited to seven of the 24 exploitation areas; that is, other extraction areas would be missing, plus related strategic areas that have not yet been explored.

Another research to study the geological issue of REEs from the Colombian perspective is entitled Petrology of the Acandí Batholith and associated bodies in Unguía-Choco, Colombia, published by Sánchez-Celis et al. (2018). According to these authors, the location of REE in sectors such as Unguía is common; the formation ofthese minerals comes from prehistoric geological processes. There are scientific aspects that are complex and involved with the production of REE; however, the question at this point responds to the location of the lanthanides. Unguía is a jurisdictional space characterized by high levels of multidimensional poverty, presence of illegal armed actors, sociological utilitarianism and illegal exploitation of mining deposits (alluvial gold).

This approach exposes issues that must be defined and explained through the national security and defense framework. However, the search for research to limit the problem shows that the knowledge published up to 2022 is scarce. The registered research reports only investigate a primary factor related to the explanation meta-conceptual of the problem REE, its relationship with geopolitics, Chinese international and macroeconomic interests and, in the Colombian case, scientific-experimental drawbacks related to the generation of wind energy (Mariev & Blueschke, 2025).

For this reason, the research focuses on three exploratory lines: establishing parameters for the relationship between tenure REE, its location in areas with high conflict values, and its possible exploitation by illegal armed actors.

In other words, the first approach will investigate the framework REE through the lens of security and defense. The second approach will analyze the problem based on the possible illicit exploitation of REE by criminal groups, generating migration of illicit mining exploitation. The third will correspond to the projection of future scenarios in which categories such as security and defense, sovereignty, protection of strategic natural resources and macroeconomic interventions by China are interconnected, to propose a Colombian national strategy for the security and defense of REE considering them as strategic natural resources.

Interpretation of the Concept of “Natural Resource Curse”, a Theoretical Approach to the Precept of National Security and Defense

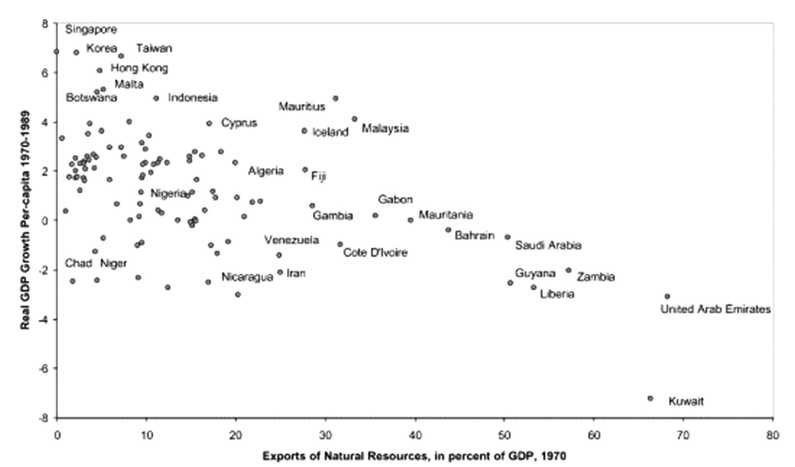

The problematic approach, structured around the concept of REE, fits into conceptual components such as the “natural resource curse.” Understanding this concept implies establishing an explanatory point of multiple conceptual contributions. A primary definition can be found in the research of Sachs & Warner (2001). According to these authors, the natural resource curse is the possession and/or holding of strategic mineral resources that, instead of boosting the country’s macroeconomic growth, diminish or slow down this process (Chapman, 2018).

The version offered by Sachs &Warner (2001) has a particularity of its own, which explains that the possession of extensive strategic areas, in which there is possession of priority resources, is not synonymous with development. On the contrary, there are enough situations to prove that the possession of resources is not enough to strengthen dominant state hegemonies. This is because exploitation, administration, and using natural resources imply more extensive and continuous investment processes (Chapman, 2018).

Now, according to Sachs &Warner (2001), the economic growth of the 1970s showed that natural resource tenure is not synonymous with exponential macroeconomic growth; nor is it a leading indicator, since tenure is part of the process by which a comparative advantage is built, but it is not sufficient to materialize it (Chapman, 2018). This is precisely what the term “curse” is all about. This term highlights macro-structural, functional, legal, security and defense, or regulatory problems that may arise from inappropriate management of strategic natural resources. Figure 7 provides an example of this course in the “GDP growth” category and the quantity of exported resources.

Figure 7. GDP over exportsgrowth.

Source: Information retrieved from Sachs and Warner (2001).

In the version provided by Sachs & Warner (2001) there is no exact explanation of the relationship between the natural resource curse, resource tenure and the concept of national security and defense. However, these contributions are helpful to understand how and under what parameters the concept of the curse is configured. A significant contribution that is aligned with the research objective is that Sachs & Warner (2001) argue that economic growth and development in countries that have a vast extension of the variable “natural resources” is not always correlated; on the contrary, case studies have shown that countries with a large amount of natural resources have demonstrated and continue to demonstrate unparalleled, slow and sometimes static growth. This same conception is stated by Posada (2015), who expresses the following:

In the middle of the 20th century, an interest in studying the growth and development of the world’s economies was awakened, especially those of the African continent. The independence of African peoples after World War II showed how the lack of industrialization and the high dependence on natural resources brought very low economic growth in most of these countries. Although abundant natural resources can mean wealth and prosperity for a nation, the inefficient exploitation of these resources causes this event to be a curse and not a blessing. (p. 124)

For Posada (2015), natural resources without precise administration are simple precepts that offer certain types of advantages to the State or government. Likewise, he brings the two concepts of the curse to the Colombian case and thus raises two interesting points of view that outline the theoretical concept towards the scenario of national security and defense (Acosta-Guzman & Jimenez-Reina, 2019; Garrido, 2020).

The first perspective explains that Colombia has ample mineral reserves. Its reserves are superior to those of other States, and this superiority lies in the possession of resources in geographical areas that have not yet been exploited (Garrido, 2020). However, keeping them unexploited is insufficient to address structural or competitive advantages. Fiscal policies that, through the reinvestment process, strengthen national industry and produce exports characterized by added value must be planned.

The second perspective is also economic-administrative and concerns export logistics costs and other structural processes, which require the government to reinvest profits to improve internationalization models. Although both perspectives deal with this issue from the economic sphere, they both refer to an interesting topic: the concentration of natural resources in territorial areas (Garrido, 2020). This concentration was taken in this research as the accumulation of minerals, hydrocarbons, and other types of resources in specific jurisdictional spaces.

The research position of this discussion is to interrelate the theory of the natural resource curse, the concentration of resources in specific areas, and related and inherent responsibilities of the national security and defense system (Koubi et al., 2014). The interconnection between natural resources and conflict is not hypothetical but accurate and characterized on certain occasions -not all- by the concentration of resources in areas prone to armed conflict (Acosta-Guzman & Jimenez-Reina, 2019). Although Koubi et.al. (2014) does not expose related variables to understand how or why conflict arises in natural resource tenure areas, conflict stemming from natural resource disputes is internal or intra-state. This statement highlights an assumption that should be investigated thoroughly, which explains that the relationship between conflict and natural resources arises from factors such as:

- First, the convergence of criminal actors, state forces and basic population needs.

- Second, the interference of criminal actors in areas where there is no security on the part of the State. This insecurity refers not only to the arms portfolio but also to food insecurity, low human development indexes, and unsatisfied basic needs, which are rising.

- Third, weaknesses in governance and governance systems. This point is important if resource tenure becomes a curse when inadequate state policies lead to improper exploitation, administration, and transformation.

The three points exposed are part of the deductive idea proposed by the author of this research, based on the contributions of Posada (2015), Koubi et al. (2014), and Acosta-Guzman & Jimenez-Reina (2019). One aspect to be noted is that, to analyze, study and explore the problem presented, it is necessary to include the national security and defense approach, which in the context of this research would turn to the precept “multidimensional security approach”.

This correlation is necessary for two reasons. First, it is imperative to characterize the term “curse” in a spectrum different from the macroeconomic one, already raised by the three previous authors. And second, because it is important to highlight that the “curse” also includes issues such as: violence in situ, increased instability factors, weak penetration of State entities and impacts that make public exercises associated with governance and governability impossible.

Conceptual Debate in Colombia on REE

The conceptual debate, as opposed to the state of the art, developed a search and cataloguing exercise of terms in four databases: SCOPUS, Web of Science, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. The search for information required creating and delimiting a methodological equation to locate associated research. The equation is as follows: * Rare Earths Elements* Colombia* research* exploitation* research* research*

With this equation, three investigations were found. The first is entitled “Geopolitics of the REE” (Álvarez & Trujillo, 2020). In this exploratory cycle, a thematic analysis was carried out based on a geopolitical version of REEs. Two conclusions, the first is that, according to emerged Álvarez and Trujillo (2020), there has been speculation about the possession of REEs in Colombia. However, there is insufficient research to determine which jurisdictional points can be found. Moreover, the authors speak of coltan as a mineral that is not exploited formally, but informally, but not of other components such as lanthanide, scandium, etc.

The second conclusion states that it is fundamental for the States to safeguard jurisdictional spaces in which there are REE. Therefore, the Colombian State must develop security strategies to preempt any geopolitical interference or transgression in REE-rich territories.

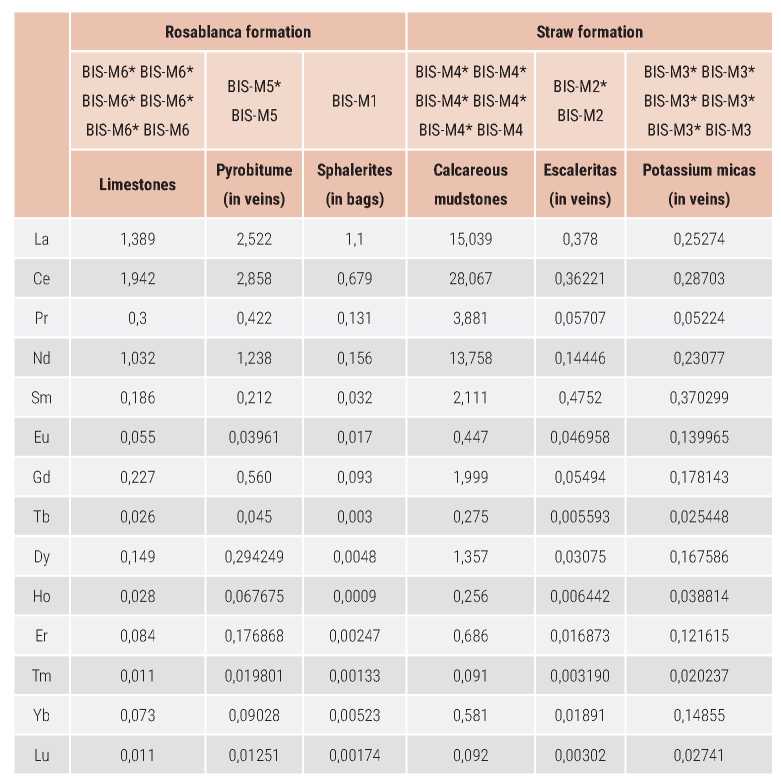

Following the research of Alvarez and Trujillo (2020), comes that of Mantilla et al. (2006). In this case, the researchers leaned towards a more scientific approach and sought to know if their elements and rocks with sediments were associated with the level of parts per million required by the qualification REE in the southern sector of Santander. Part of the findings obtained by the authors affirm that REE exists in the referential sector, especially in potassic micas and pyrobitumen-type materials. Table 3 shows the results obtained by this group of researchers.

Table 3. Characterization of elements found.

* See aspect of these materials in Mantilla et al. (2003a).

Source: Information retrieved from Mantilla et al. (2006)

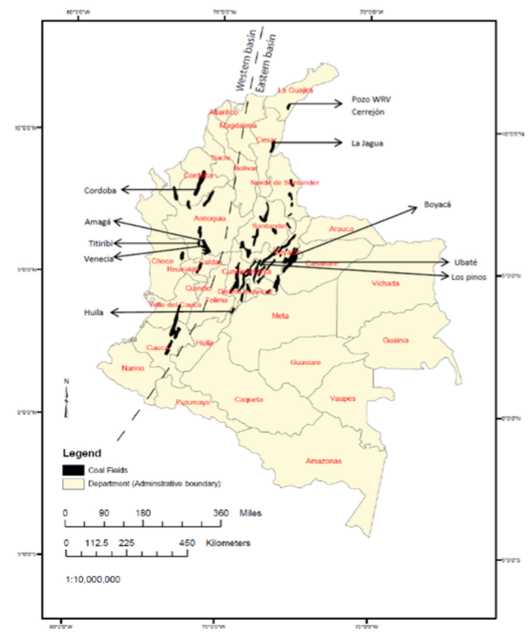

In their research, Mantilla et al. (2006) prove that there are lanthanides in Colombian territory, but they have not yet been quantified, a fact that disadvantages the country. Now, the final research is that of Henao (2019), and it not only reaffirms the existence of REE, but also provides its location. The result shows the geographical composition of lanthanides found in Huila, Tolima, Antioquia, and Cundinamarca coal rocks. This research analyzed minerals on coal rocks in the geographic reference of the following map (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Map of coal extraction sites with REE.

Information retrieved from Henao (2019)

The existence of REE in Colombia, although still under investigation, is undeniable, and the last two studies show it. Now, a significant contribution in the case of Alvarez and Trujillo’s research (2020) is the need for the State to structure a model or strategic line of security that can safeguard and protect the lanthanides located in Colombian territory in advance. To this end, this research is delimited through a qualitative search method, with the geographic points with generalized locations of lanthanides, according to the information provided by the open databases and the information system of the Colombian Geological Service.1

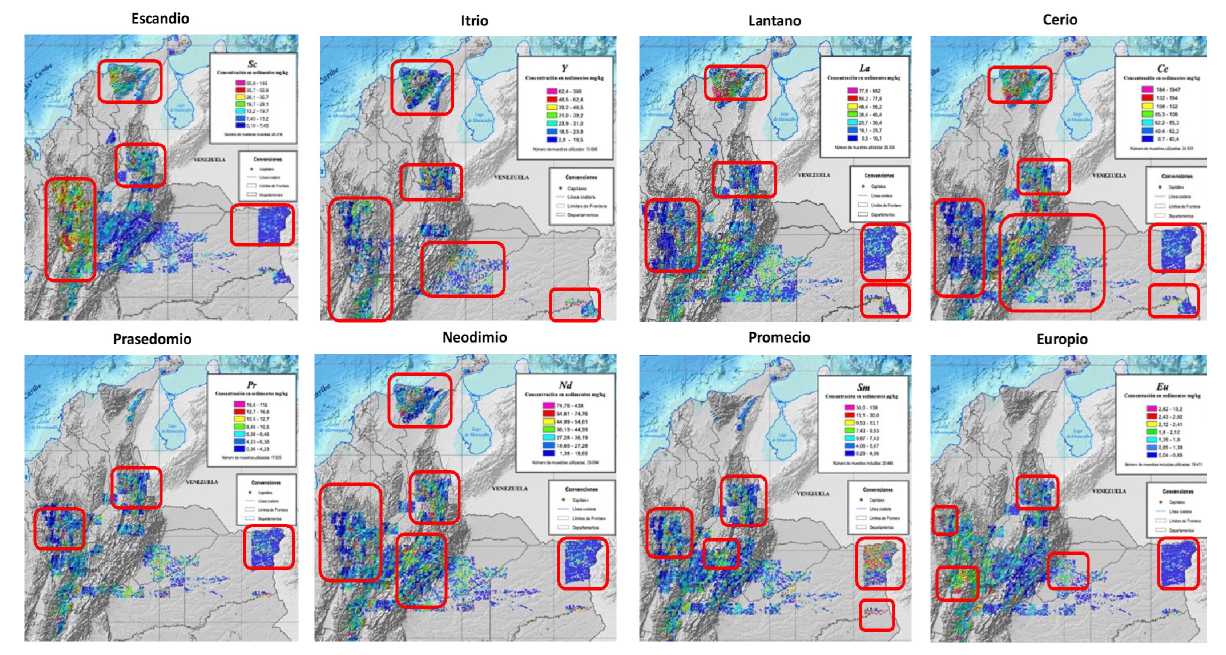

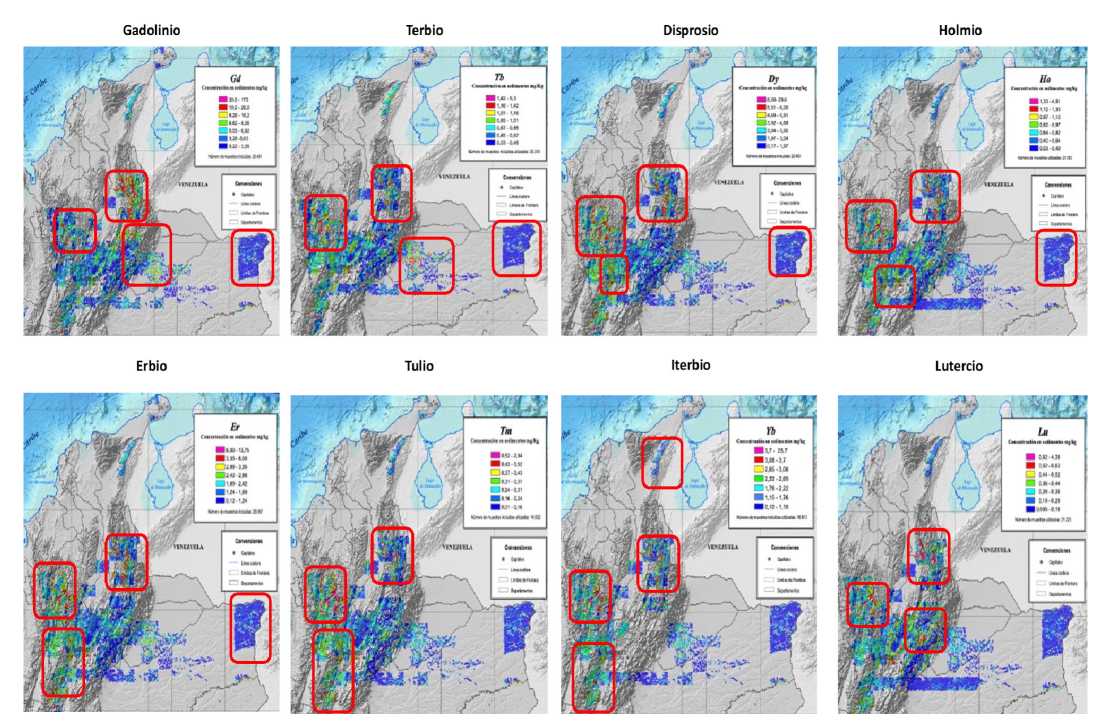

The methodological process begins by locating REE from the geolocation of the two chemical elements (scandium and yttrium) and the other 15 lanthanides. The results obtained are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9a. REE. Elements located in Colombian territory.

Source: Own elaboration with information retrieved from the Colombian Geological Service (2022).

Figure 9b. REE. Elements located in Colombian territory.

Source: Own elaboration with information retrieved from the Colombian Geological Service (2022).

As can be seen, the location of chemical elements and lanthanides2 in Colombian territory presents two patterns. First, 95% of the components are in Norte de Santander (southern sector, border with Venezuela), Vichada (Puerto Carreño sector, border with Venezuela), Tolima, Meta, and on the Sierra de Santa Marta National Park.

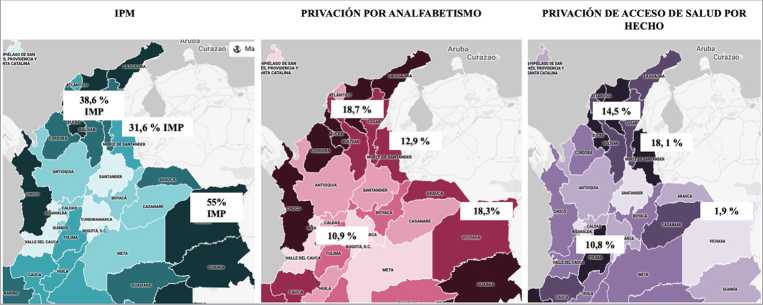

Second, in Norte de Santander and Vichada, 16 of the 17 components that make up the concept converge with REE. Now, with the georeferencing of components, we move on to the next phase, which corresponds to the identification of socioeconomic and armed instability factors that coexist in the five referenced sectors. The georeferencing software used the Administrative Department of National Statistics for this part of the exercise. The search for socioeconomic instability factors will focus on five essential aspects: multidimensional poverty index (MPI), unsatisfied basic needs (UBN), monetary poverty, deprivation due to illiteracy (AP) and deprivation of access to health due to events or obstacles (Figure 10).

Figure 10. IPM, PA and PASH indicators.

Source: Own elaboration with information retrieved from the Colombian Geological Service (2022).

The first three indicators assume that, as in the case of other contexts where there is illegal exploitation of mining deposits, the highest concentration of components that make up the category REE are in strategic border areas with high rates of multidimensional poverty. Such is the case with Vichada (55%) and Norte de Santander (31.6%). In addition, and as in the case of the location of armed instability factors, some components are in geographic spaces with a wide margin of illiteracy and deprivation of access to health due to obstacles and related events. See, for example, Tolima (10.9%) or Norte de Santander (12.9%).

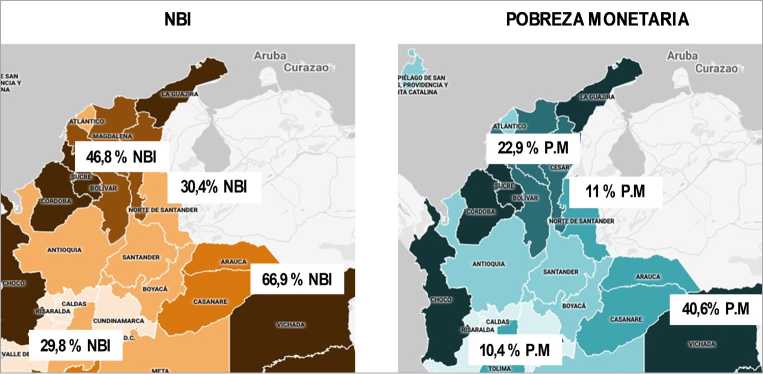

The indicators recorded are high and bring a historical record that, although decreasing in the case of the MPI, is still not enough. This risks the population actors living in territories with a significant presence of components associated with the concept of REE and puts them in a state of vulnerability. However, to support this statement, other important variables, such as unsatisfied basic needs (UBN, NBI in Spanish), must also be included (Figure 11).

Figure 11. UBN and monetary poverty.

Source: Own elaboration with information retrieved from DANE (2022).

The figure shows that the UBN level in Vichada, a sector where there is a high concentration of scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, neodymium, praseodymium and europium, is exceptionally high, reaching a percentage of 66.9%. Another critical sector is Norte de Santander, a geographical area with high volumes of cerium, lanthanum, gadolinium, neodymium, ytterbium, lutetium and erbium. Similarly, the Tolima sector, with an index of 29.8%. However, the monetary poverty index must also be a sensitive factor to this indicator. Vichada has an added multidimensional poverty level of 40.6%, Norte de Santander 11% and Tolima 10.4%.

The list of indicators presented up to this point suggests that, as with other crimes, criminal behavior and terrorist actions, the risk of illicit extraction of chemical elements and lanthanides is high. This is due to three causes: multidimensional poverty, which reduces the developmental capacity of the population and government institutions; the breakdown of regional systems designed for the exercise of governance and governability; and a high UBN index, a factor that reduces the quality of life and collective wellbeing of a socioeconomically vulnerable population.

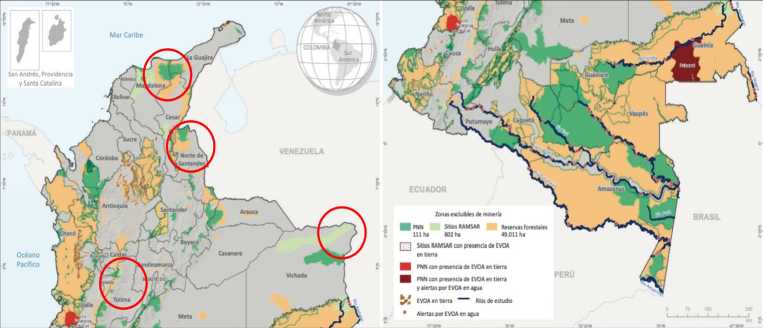

However, to complement this analysis, other variables must be added to geo-referenced data to determine which armed instability factors are found in the zones of interference (areas with REE). To this end, three key factors must be studied: the illicit extraction of alluvial gold and its geo-referencing, illegal coca leaf cultivation and the presence of armed actors in the territory (ELN, as an example) (Acosta-Guzman & Jimenez-Reina, 2019).

With respect to the phenomenon of illicit alluvial gold mining, it must be recognized that, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2021) there are territorial areas with a significant presence and processes of illicit mining; however, according to the information recorded in its georeferenced, these are not located in areas of influence containing elements and lanthanides, as can be seen in the map (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Map of illicit extraction of mining deposits (alluvial gold mining [EVOA]).

Source: Information retrieved from UNODC (2021).

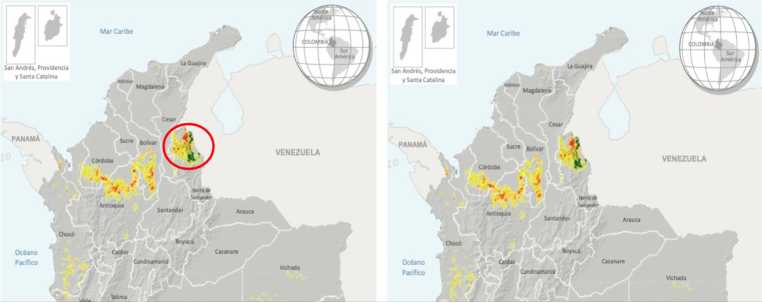

A different situation occurs in the cultivation of illegal coca leaf. Here, it is necessary to underline the significant presence of illegal coca leaf crops in Norte de Santander, where 16 ofthe 17 components are present. As seen in the following map (Figure 13), this volume increased in the subregion of Catatumbo between 2019 and 2020.

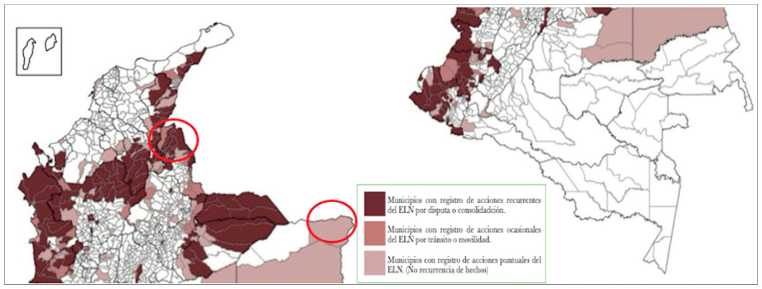

The same situation occurs with armed instability factors from the National Liberation Army (ELN by its initials in Spanish), as seen in the following map (Figure 14).

Figure 13. Map of illicit crops.

Source: Information retrieved from UNODC (2021).

Figure 14. Location of ELN structures.

Source: Information retrieved from Indepaz (2020).

The criminal structures—the ELN, for that matter—are currently in trending areas. Two of these zones are critical: Norte de Santander and Puerto Carreño, in Vichada. These zones also have high rates of multidimensional poverty, low human development indexes, and other instability factors not included in this research section.

Conclusions

As could be agreed, multiple factors converge in the problem. One of them, perhaps the most important, is the recognition of the existence and georeferencing of REEs in Colombia.

Three key regions for this analysis are Norte de Santander, Vichada, and Tolima. Their importance lies not only in the existence of REE but also in the confluence of armed and economic instability factors that favor criminal phenomenology, such as the illegal extraction of mining deposits, an activity that could be assimilated with the illegal extraction and exploitation of REE in possible future scenarios.

In addition, two of the three zones are in border areas. This warns not only of illicit extraction by Colombian criminal groups but also of geopolitical and border transgression by transnational criminal actors who see and find a geostrategic and geographic advantage in the porosity of borders.

However, one of the most relevant perspectives, which emerges with the contribution of Alvarez and Trujillo (2020), is that strategic anticipatory actions should protect areas with extensive natural resource tenure. The intervention or anticipation process must be annexed to national security and defense policy since, as has been shown, the control of geographic spaces with REE is a socio-environmental, socio-cultural, and socio-political goal, interest, and objective of the Colombian State.

From a scientific perspective, the REEs and their exploration and location in Colombian territory are just beginning. This is an opportunity for the State to develop processes of intervention and analysis of intersectoral typology to prevent criminal phenomenology, such as an increase in hectares of illegal coca leaf cultivation because of economic and armed instability factors or illicit exploitation of mining deposits.

If the State does not anticipate scattered criminal phenomenologies with probability of fulfillment, the structural concept that brings with it the curse of natural resources would be configured for a future scenario.

Aknowledgments

The author would like to thank US Naval War College for their support in the completion of this article.

Disclosure statement

The author declares that there is no potential conflict of interest related to the article. This article is from Master’s Degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from U.S. Naval War College.

Financing

The author does not declare a source of financing for the completion of this article.

Author

Jorge Alfonso García Torres. Commander of the Colombian National Navy. Master’s Degree in National Security and Defense, Colombian War College “General Rafael Reyes Prieto”. Master’s Degree in Politics and International Relations, Sergio Arboleda University, Colombia. Fellow of the William Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies, USA. Master’s Degree Candidate in National Security and Strategic Studies, U.S. Naval War College.

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7688-4895 - Contact: jorgartorr@gmail.com

1 By means of a virtual request made on the Colombian Geological Service portal, updated and registered geographic information was obtained about interest: location of minerals and lanthanides.

2 This term is hereinafter referred to as “components”.

References

Acosta-Guzman, H. M., & Jimenez-Reina, J. (2019). La geopolítica criminal de los grupos armados organizados. In C. A. Ardila-Castro & J. Jimenez-Reina (Eds.), Convergencia de conceptos: Enfoques sinérgicos en relación a las amenazas a la seguridad del Estado Colombiano (pp. 85-115). Sello Editorial ESDEG. https://doi.org/10.25062/9789585698307.03

Álvarez, C., &Trujillo, J. (2020). Geopolitics of rare earth elements: A strategic natural resource for the multidimensional security of the state. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 18(30), 335-355.

Bortolini, C. (2020). Will there be a war for rare earths? Strategic resources at the center of the China-U.S. conflict. Le Monde diplomatique en español, 297, 24.

Chapman, B. (2018). The geopolitics of rare earth elements: Emerging challenge for U.S. national security and economics. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 6(2), 50-91. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME6220182

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE). (2022, January 12). Geovisor indicadores regionales. https://tinyurl.com/2chayka9

Dos Fuser, L. N. S. (2023). The geopolitics of rare earth elements (REEs) and the insertion of Brazil. Geopolitica(s), 14(1), 27-50. https://doi.org/10.5209/geop.79921

European Commission. (2020, September 3). Critical raw materials resilience: Charting a path towards greater security and sustainability. https://tinyurl.com/yblog9or

Fernández, R. (2022, June 17). Percentage of U.S. rare earth imports by country 2017-2021. https://tinyurl.com/25xy5lvg

Gabás, N. E. (2020). Geostrategic consequences of China’s hegemony in the rare earth market. Global Strategy Report, 1-10.

Gadea-Ugarte, O. (2020). Objective: Rare earths. A review of the book La guerra de los metales raros by Guillaume Pitron. Revista de Química, 34(1-2), 38-39.

Gao, W., Wei, J., Zhang, H., &Zhang, H. (2024). The higher-order moments connectedness between rare earth and clean energy markets and the role of geopolitical risk: New insights from a TVP-VAR framework. Energy, 305, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.132280

Garrido, M. L. (2020). Natural resources and security in Latin America: An emerging security problem. Revista de Pensamiento Estratégico y Seguridad CISDE, 5(1), 11-28.

Ghorbani, Y., Zhang, S. E., Bourdeau, J. E., Chipangamate, N. S., Rose, D. H., Valodia, I., &Nwaila, G. (2024). The strategic role of lithium in the green energy transition: Towards an OPEC-style framework for green energy-mineral exporting countries (GEMEC). Resources Policy, 90, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2024.104737

Grasso, V. B. (2013). Rare earth elements in national defense: Background, oversight issues, and options for Congress. Library of Congress.

Haxel, G. (2002). Rare earth elements: Critical resources for high technology. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

Henao, J. (2019). Identificación de elementos de tierras raras en carbones colombianos. Escuela de Ingeniería de Materiales.

Hirschman, A. O. (1980). National power and the structure of foreign trade. University of California Press.

Humphries, M. (2010). Rare earth elements: The global supply chain. Diane Publishing.

Hyatt, A. (2024). Framing China’s strategic mineral dominance: Insights from Chinese state media. Obrana a Strategie, 24(2), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.3849/1802-7199.24.2024.02.77-97

Indepaz. (2020, February). Balance on the dynamics of the Ejército de Liberación Nacional -ELN- in Colombia 2018, 2019 and 2020-I. Indepaz.

Ketris, M., & Yudovich, Y. (2009). Estimations of Clarkes for carbonaceous biolithes: World averages for trace element contents in black shales and coals. International Journal of Coal Geology, 78(2), 135-148.

Koubi, V., Spilker, G., Bohmelt, T., & Bernauer, T. (2014). Do natural resources matter for interstate and intrastate armed conflict? Journal of Peace Research, 51 (2), 227-243.

Mantilla, F. L., Tassinari, C. C., & Mancini, L. H. (2006). Study of C, O, Sr isotopes and rare earth elements (REE) in Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of the Eastern Cordillera (Santander Department, Colombia): Paleohydrogeological implications. Boletín de Geología, 28(1), 61-80.

Mariev, O., & Blueschke, D. (2025). Interplay of Chinese rare earth elements supply and European clean energy transition: A geopolitical context analysis. Renewable Energy, 238, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.121986

Martins, T. T. (2024). Rare earth geopolitics: Global dynamics and strategic balance of power. Janus.net, 15(1), 249-265. https://doi.org/10.26619/1647-7251.15.1.14

Pérez, E. (2018). Developmentalism and rare earths: Origins and causes of extractivism in China. Papeles de Relaciones Ecosociales y Cambio Global, 119-136.

Posada, J. (2015). The curse of natural resources: Symptoms and consequences in the external sector. Revista Civilizar de Empresa y Economía, 6(11), 123-142.

Reboredo, R. P. (2021). Rare earths: A key piece in the energy puzzle. Energía y Geoestrategia, 309-378.

Riesgo, M. V. (2020). Investment in rare earth mining: Preliminary economic evaluation of mining projects for a critical raw material for the European Union. http://hdl.handle.net/10259/6637

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (2001). The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45(4-6), 827-838.

Sánchez, D. (2012). Mining-energy dependence: The case of Germany-Russia. Energetic Society, 34-39.

Sánchez-Celis, D., Frantz, J., Charão-Marques, J., & Barrera-Cortés, M. (2018). Petrology of the Acandí Batholith and associated bodies, Unguía-Chocó, Colombia. Boletín de Geología, 40(1), 63-81.

Servicio Geológico Colombiano. (2022, January 12). File download service.

SWI. (2022, January 15). U.S. senators want to reduce dependence on China for rare earth imports. https://tinyurl.com/2azpcb5u

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2021). Colombia. Alluvial gold exploitation. Evidence based on remote sensing 2020. UN and UNODC Publication.

Vekasi, K. (2021). The geoeconomics of critical rare earth minerals. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 22(2), 271-279.

Villamuera, J. (2021, May 11). El Orden Mundial. What are rare earths in the technological war? https://tinyurl.com/2bu5fzs4

Wang, P., Yang, Y.-Y., Heidrich, O., Chen, L.-Y., Chen, L.-H., Fishman, T., & Chen, W.-Q. (2024). Regional rare-earth element supply and demand balanced with circular economy strategies. Nature Geoscience, 17(1), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01350-9

Weber, D. A. (2021). The geopolitical impact of rare earths in the international order. Economía Industrial, 420, 47-58.

World Trade Organization. (2014, March 26). China - Measures related to the exportation of rare earths, tungsten, and molybdenum: Reports of the panel. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/431_432_433r_e.pdf